Businesses dynamics have undergone a metamorphosis with its whetting appetite for adoption of technology and digitisation. An asymmetric transition in the income-tax laws, however, seem to have muffled the potencies of this digital juggernaut leading to a myriad litigations on this space before courts and tribunals. With software playing a quintessential role in the digital world, striking a chord between the current income-tax laws and the multiple facets/ contours of software, further exacerbates challenges for the tax administrators and judiciary. Although the Finance Act, 2012 introduced Explanation 4 to Section 9(1)(vi) of the Income Tax Act, 1961 (‘Act’) with retrospective effect to inter alia clarify the inclusion of right to use computer software (including granting of a licence) within the definition of “Royalty”, not much air is cleared around taxation of new-age cloud computing or software models, leaving the door ajar for debate.

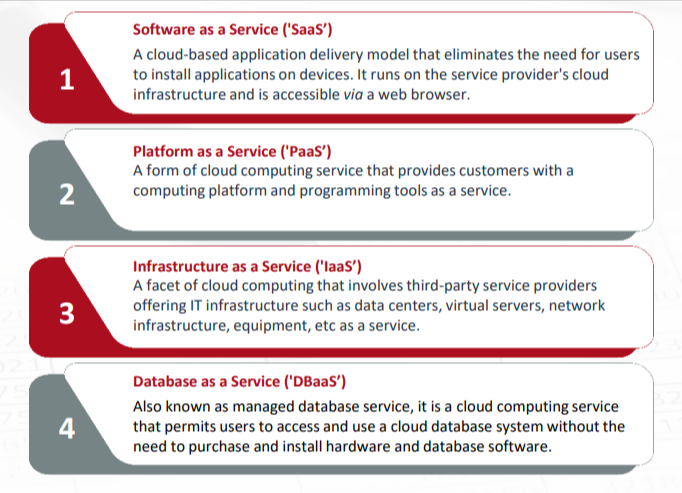

Taxpayers have been grappling with interpretational issues while sewing a generalized and wide definition of “Royalty” provided under Indian Income tax laws read with Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (‘DTAA’ or ‘Tax Treaty’) in cross border transactions, with diversities, variants and specifications of each software model in the emerging landscape of ITeS and cloud-based services. With a service element interspersed into these models, evaluation of taxation of software “as a service” also becomes instrumental. Broadly categorized, these cloud computing models include:

Our Professionals

Sandeep Jhunjhunwala

Partner

Amita Jivrajani

Director

Udit Jain

Manager

Merlin Maleques

Associate

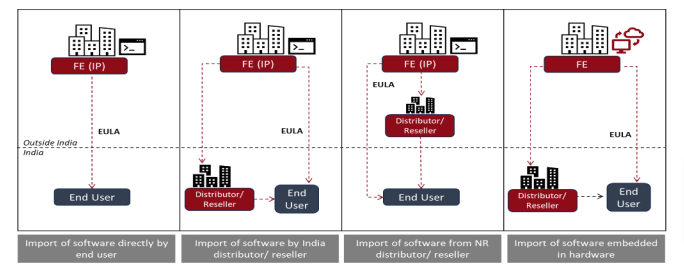

For most taxpayers, the controversy around taxation of “Software” seems to have been allayed by the Supreme Court (‘SC’) in its landmark ruling in the case of Engineering Analysis Centre of Excellence (P) Ltd vs CIT1 which put a happy end to an age-old dispute on taxation of cross-border payments made for the import of software for sale in India, by delivering a judgement in favour of the taxpayers. However, the cult status of this ruling may soon recede in an era of ballooning kaleidoscopic software models as the Hon’ble Apex Court has, in the assortment of appeals, analysed payments made for use of shrink-wrapped computer software by the end-user or distributor under an End User License Agreement (‘EULA’) or distribution agreement falling within the following 4 specific categories.

The question, hence, arises on whether the Hon’ble Apex Court ruling in Engineering Analysis (supra) could squarely be applied when determining the taxability of the new-aged software-based service delivery models. Although the SC judgement lays to bed a two-decade old litigation, the contemporaneousness of which may test waters, many vital aspects around inter alia, interpretation of DTAAs, interplay between the copyright law and the scope of Indian income-tax laws, importance and relevance of OECD2 commentaries, emerge from the ruling. Hence, the Hon’ble SC cannot be said to be a day late and a dollar short on the judgement as the principleslaid down and interpretations drawn (discussed below) could have a staunch persuasive value in determining the taxability of products/services in the current technological reign.

Principles emanating from the SC ruling on software taxation, in a nutshell

In essence, the Hon’ble SC laid down the following key principles to negate the imposition of “Royalty” taxation on shrink-wrapped computer software:

-

Interplay with the Copyright Act, 1957 (‘Copyright Act’):

- In the context of computer software, transfer of “all or any rights (including the granting of license) in respect of any copyright” as stated in Section 9(1)(vi) of the Act, is referable to Section 143 of the Copyright Act

- Parting with copyright entails parting with the right to do any of the acts mentioned in Section 14 of the Copyright Act. Transfer of the material substance in which the copyrighted work is embodied does not itself serve to transfer the copyright therein (distinction between copyrighted article and copyright)

- Where the core of a transaction is to authorise the end user to have access to and make use of the “licensed” computer software product (over which the licensee has no exclusive rights), no copyright is parted with. It makes no difference whether the end user is enabled to use computer software that is customised to its specifications or otherwise

- A non-exclusive, non-transferable licence, merely enabling the use of a copyrighted product, is in the nature of restrictive condition which is ancillary to such use, and cannot be construed as a licence to enjoy all or any of the enumerated rights mentioned in Section 14 of the Copyright Act, or create any interest in any such rights so as to attract section 304 of the Copyright Act

- The right to reproduce and the right to use computer software are distinct and separate rights, as has been recognised in the decision of State Bank of India5, the former amounting to parting with copyright and the latter, in the context of non-exclusive EULAs, not being so.

-

Exhaustive definition of “Royalty” as per Tax Treaty

Definition of “Royalty” in Tax Treaties which are mostly similar to the OECD or UN Model Tax Convention are exhaustive vis-à-vis the expansive definition provided under the Act and cannot be given a go-bye. Further, the definition of “Royalty” in the DTAA would be constrained by the definition of the term “Copyright” under Section 14 of the Copyright Act as used therein.

-

True effect of a transaction determines the taxability

The license granted by the sellers, in a sense, is a sale of a physical object which contained an embedded computer program and hence a sale of goods. Designation given to a transaction is not a decisive factor, and the true effect of the agreement needs to be considered, taking into account the overall terms of the agreement and relevant circumstances.

-

Distinction between Copyrighted article and Copyright

The Hon’ble SC upheld the law declared in the case of Tata Consultancy Services vs State of AP6 that classified shrink-wrap/ packaged software as goods in the context of sales tax statute. Distinction drawn between transactions involving sale/ use of copyrighted products, as opposed to transactions granting rights in the underlying copyright itself.

-

OECD commentary has persuasive value

Most of India’s tax treaties are based on the OECD Model Tax Convention. As regards the interpretation of the term “Royalty”, the OECD commentary inter alia provides that, in case of arrangements between a software copyright holder and a distribution intermediary to distribute copies of the programme without the right to reproduce that programme, distributors are paying only for the acquisition of the software copies and not to exploit any right in the software copyrights. Thus, the rights in relation to these acts of distribution should be disregarded in analysing the character of the transaction for tax purposes. The Hon’ble SC had further held India’s reservation with respect to OECD commentary would not have tax implications unless the relevant Tax Treaty undergoes a change.

Binding effect of the Apex Court ruling considering the Review Petition

It is pertinent to note that a review petition has been filed against the Engineering Analysis (supra) ruling. A question arises as to the binding effect of the Apex Court ruling, given the pending adjudication of the review petition. In this regard, SC in the case of MOL Corporation7 being cognizant of the pending review petition, affirmed that the precedent set by the Engineering Analysis (supra) ruling would prevail and if the matter raised in special leave petition is allowed, then this leave petition may be revived at the petitioner’s discretion. Further, SC in the case of Gracemac Corporation8 being cognizant of pending review petition held that the Engineering Analysis (supra) ruling would hold field and if the judgement is overruled, its impact would be confined to the Engineering Analysis (supra) decision and the cases to be decided thereafter.

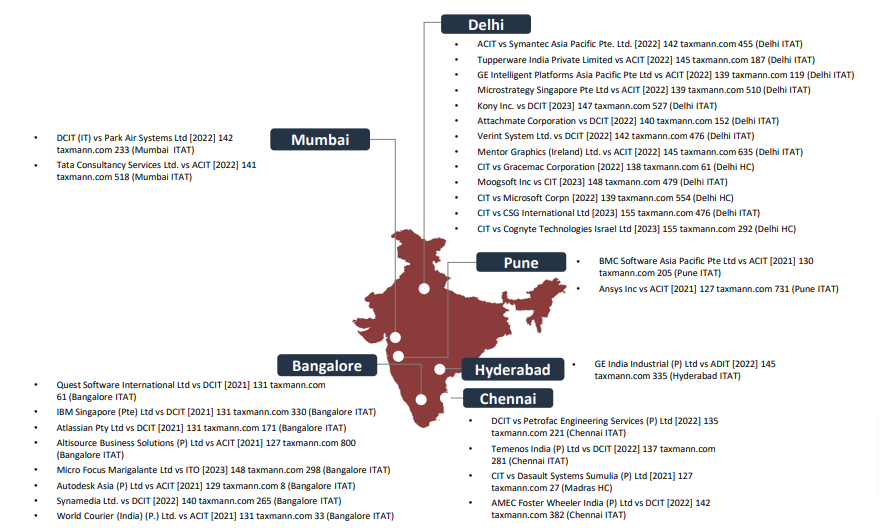

Snow balling effect of the SC ruling on software payments

Listed below are the rulings in which the facts bear a resemblance to categories of software transactions mentioned in the Apex Court ruling, and as a result, the principles are directly applied to affirm the non-applicability of Royalty taxation:

Bearing on new age software transactions

The taxation of IT based services and their variants have always been a typhoon in the emerging landscape of ITeS and cloud-based services and Courts today are battling the headwinds. Tribunals have, while adjudicating on taxability of payments made for database subscription, web hosting, online advertisement, and other cloud computing models relied upon Engineering Analysis (supra) case and held that such payments should not be considered in the nature of “Royalty”, albeit with no specific inferences drawn from the principles laid down therein.

Citations of few such rulings are enumerated below:

| Database Subscription | Online Advertisement and Marketing | Webhosting and Cloud Computing |

|---|---|---|

| American Chemical Society vs DCIT [2023] 146 taxmann.com 133 (Mumbai ITAT) | Urban Ladder Home Décor Solutions Private Limited [TS 773-ITAT-2021] (Bangalore) | Amazon Web Services, Inc vs ACIT [TS-419-ITAT 2023(Delhi)] |

| Pluralsight LLC vs DCIT [TS477-ITAT-2023 (Bangalore ITAT)] | Google India Private Limited vs DCIT [2022] 143 taxmann.com 302 (Bangalore ITAT) | MOL Corporation vs DCIT [2022] 137 taxmann.com 286 (Delhi ITAT) |

| Uptodate Inc vs DCIT [2023] 150 taxmann.com 231 (Delhi ITAT) | Matrimony.com Limited vs ACIT/DCIT/ITO [2023] 148 taxmann.com 470 (Chennai ITAT) | Infosys Limited vs DCIT [ITA No 105 to 115/Bang/2021 (Bangalore ITAT)] |

| OVID Technologies Inc vs DCIT [2022] 138 taxmann.com 229 (Delhi ITAT) | ESPN Digital Media (India) (P) Limited vs DCIT [2022] 140 taxmann.com 442 (Chennai ITAT) | Lemnisk Private Limited vs DCIT [2022] 141 taxmann.com 195 (Bangalore ITAT) |

| EduNxt Global SDN BHD vs ACIT [2022] 144 taxmann.com 62 (Bangalore ITAT) | Google Ireland Ltd vs DCIT [2023] 148 taxmann.com 106 (Bangalore ITAT) | |

| Myntra Designs Private Limited vs DCIT [ITA No 598 to 600/Bang/2020 (Bangalore ITAT)] |

It would be important to note that the Tribunals in the aforesaid rulings coherently rely upon the Hon’ble SC ruling in the case of Engineering Analysis (supra) without going down the rabbit hole on the principles emanating therefrom and their applicability to the facts in hand. An exception, would however be, the ruling in the case of Bekaert Industries Private Limited vs DCIT [ITA No 1003/PUN/2017] delivered by the Pune Tribunal wherein it was held that payment for full-fledged IT infrastructure facility in the nature of equipment with the help of ERP system (SAP), SAP platforms, hardware, software, servers, network, domain structures and security, would be taxable as “Industrial Royalty” and would not be covered by the decision of the Hon’ble SC.

Factors to be kept in mind in evaluating software taxation matters

Without prejudice to any of the above, the following key factors are noteworthy that could be borne in mind while evaluating the applicability of ‘Royalty’ taxation in respect of software payments:

- As the DTAA provisions take precedence over the provisions of the Act to the extent they are beneficial, the taxability of every transaction has to be analyzed as per the DTAA provisions as well. To avail the benefits of the DTAA, one should have the relevant documents such as Tax Residency Certificate (‘TRC’), Electronic Form 10F, No Permanent Establishment (‘PE’) Declaration, etc.

- The meaning of the term “Copyright” in the “Royalty” definition should be derived from the provisions of the Copyright Act. As per the Copyright Act, “Copyright” means an exclusive right to do or authorize to do certain acts including an exclusive right, inter alia, to reproduce the copyright in the work in any material form by way of sale, transfer, license, etc.

- The following parameters become imperative to establish that there is no transfer of copyright and hence, contractual arrangements should adequately document clauses to this effect:

- License granted to distributor/ end-user is a non-exclusive and nontransferable license and no copyright is transferred either to the distributor or to the ultimate end user

- No right has been granted to sub-license or transfer, nor is there any right to reverse engineer, modify, reproduce in any manner otherwise than permitted by the licence to the end user. No proprietary interest on the licence is conferred on the distributor/ end-user

- One may make a copy of the software in a machine-readable form for backup purposes only, provided that the backup copy must include all copyright or other proprietary notices contained on the original purposes

Way forward for taxpayers

In the dynamic realm of software business models, businesses witness daily emergence of new innovations and previously uncharted features. As intricacies of these software business models are navigated, it becomes clear that assessing income tax implications is a contemporary and multifaceted task, given the complex nature of income tax regulations and the ongoing disputes. With an uncertain tax climate, the following oars could come handy to taxpayers for sailing through the choppy waters.

- Conducting a comprehensive review of inter-company and third-party agreements for software licences, use of platforms, subscriptions, etc resulting in India-sourced income and analyse withholding tax/ taxability positions taking cognisance of established judicial principles. Such evaluation would also be imperative for inter-company cross charges on centrally procured software licences.

- Non-resident software service/ cloud service providers could exchange communications with Indian customers to align on the withholding tax positions prior to processing of payments to mitigate tax leakages. Nonresident vendors should inter alia ensure that the necessary documents to claim Tax Treaty benefits (TRC, electronic Form 10F, No PE declaration) are provided to the deductor/ payer/ Indian customer in a timely manner.

- Non-resident software service/ cloud service providers could consider applying to the Indian Tax Authorities to obtain a ‘Nil’ withholding order by placing reliance on established judicial principles [application under Section 195(2) of the Income Tax Act].

- Foreign enterprises encountering instances where Indian customers have withheld taxes on a conservative basis could consider taking a position in the return of income, where applicable, and claim a credit/ refund of the taxes withheld in India.

- Evaluating applicability of the Equalization Levy 2.0 (‘EQ Levy’) is paramount too. With effect from April 1, 2020, an EQ Levy of 2 percent was introduced on goods supplied/ services provided/ facilitated by non-residents to India through an electronic platform. Consideration which is otherwise not taxable as ‘Royalty’ or ‘Fees for technical services’ under the Act, could be subject to 2 percent EQ Levy. If basis the analysis conducted, the non-resident vendor is of the view that the consideration receivable against its software services is not taxable as ‘Royalty’ in India, it would be imperative to examine whether the same could be subject to 2 percent EQ Levy.

- For software distributors/channel partners, a “no” withholding tax position under Section 195 of the Act on procurement from non-resident software vendors could be applied, following the principles established by the Hon’ble Apex Court. This approach renders the impact of Notification No 21/20129 issued to nullify the cascading effect of tax withholding, ineffective. In such cases, distributors/ channel partners could consider obtaining a lower/ Nil withholding certificate qua the payments receivable from Indian customers on onward distribution of the software.